Stable coins: Just other monetary liabilities

20 May 2022

The recent pressure on some stable coins like tether seems to reveal underlying weaknesses in their specific set-ups. Similar events like bank runs, currency crises, “circuit breakers,” “breaking the buck” and “gating” are indicative that undue pressures may afflict any monetary and investment arrangement.1 Stable coins are no different than other monetary liabilities like bank deposits or money market fund units. They offer important additions to the range of available monies and form part of a broader trend towards increasing diversification and choice in payments. But there is room for improvement.

Stable coins have suffered pressures amid a recently more volatile market environment. Other similar monetary arrangements have not. This seems to indicate that confidence in stable coins remains fragile. It is likely due at least in part to a lack of corresponding regulation. Above all poor communication by stable coin issuers risks depleting trust more precipitously. However, there are no inherent flaws in stable coin arrangements but there are inherent risks.

Stable coins pegged to a national currency represent a claim to convert a given amount at par and on demand into the national currency (algorithmic stable coins are very different and excluded herein). They are normally issued as digital representations of value on blockchain or other distributed ledger technology platforms to serve as native payment instruments for blockchain-enabled financial ecosystems. In principle the peg is ensured if sufficient assets are kept that can be liquidated in time and without impairment of value to meet redemption requests. Banks, money market funds, fixed exchange rate regimes suffer from similar “redemption at par risks.”

Banks are tightly regulated to ensure they can sustain convertibility. A bank deposit is a claim on a bank denominated in a national currency. Banks need to ensure they keep sufficient liquid assets to allow customers to convert their holdings into national currency at any point in time. Banks are set-up to meet small redemption requests but would struggle if a large number of customers were to seek redemption at the same time. This is because a bank’s assets are often long-dated and cannot be liquidated at short notice. Back-stop facilities from central banks exist to ensure banks have sufficient currency but bank runs exist (Northern Rock).

Money market funds equally are subject to onerous regulation to ensure they can meet redemption requests during trading times. Depending on the type of money market fund, regulation can be highly prescriptive as to the assets money market funds can hold. However, they may hold assets that lose value meaning the net asset value of the fund could drop below par, breaking the buck, leading to no longer being able to redeem a money market fund unit at par (Reserve Primary Fund).

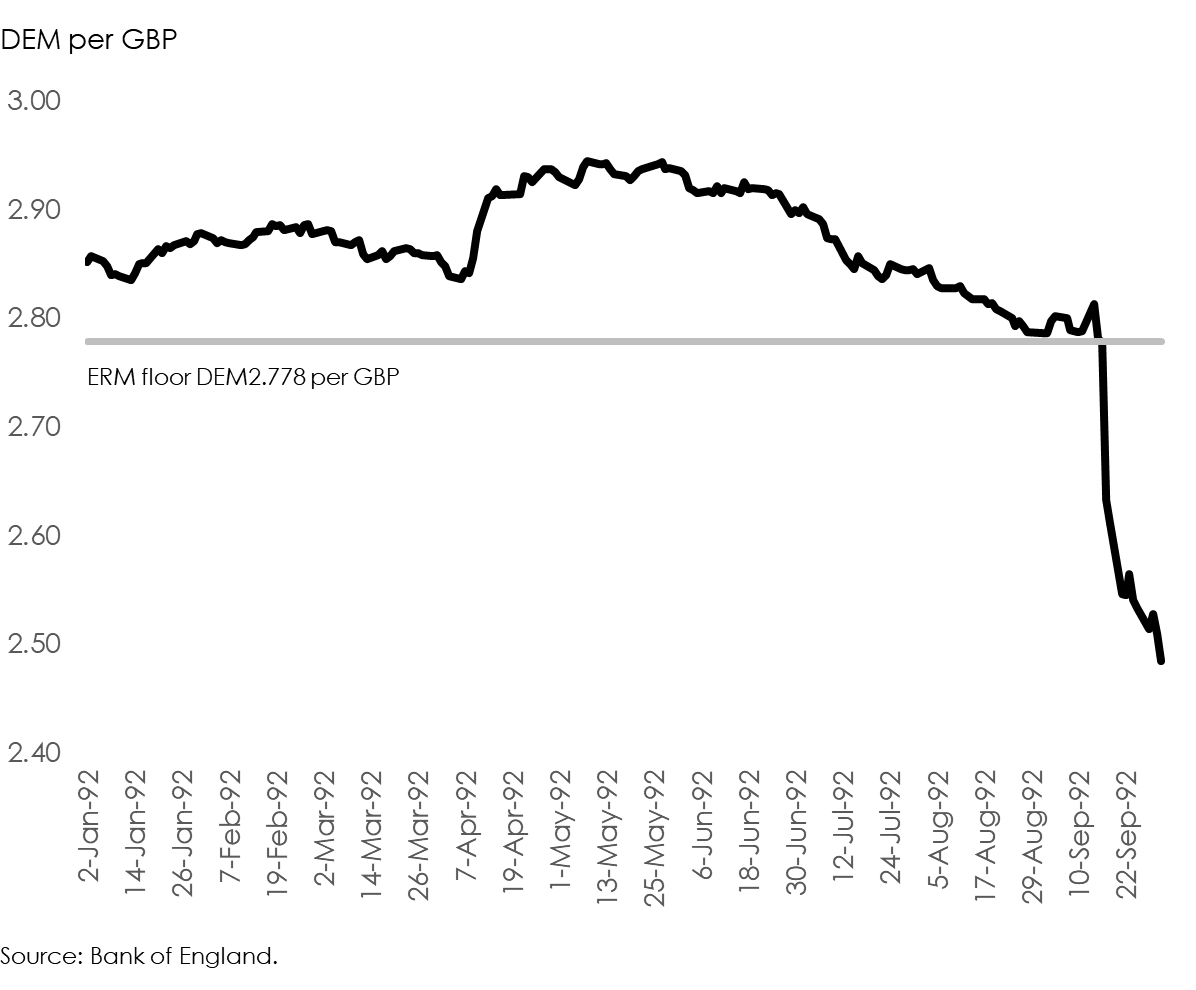

Fixed exchange rate regimes are normally commitments to maintain the value of a currency at a preannounced exchange rate. To convey confidence that the exchange rate peg can be maintained, central banks maintain large amounts of foreign exchange reserves (the composition thereof is normally not disclosed in detail). However, collapses of fixed exchange rate regimes occur (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sterling

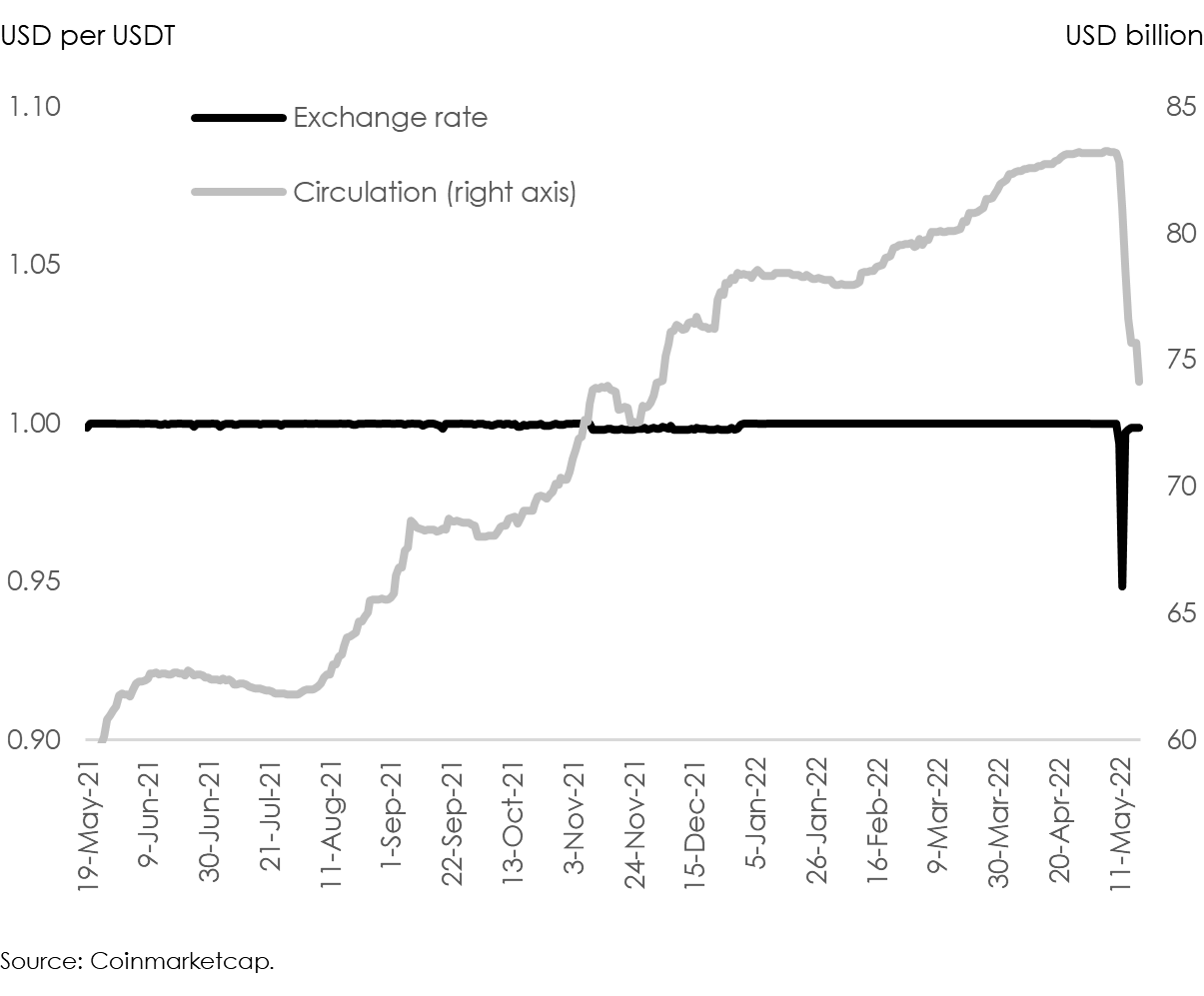

The recent pressures on stable coin tether and brief slippage of the peg remind of potential fragilities of some stable coin arrangements. Tether recovered promptly to trade at par and there does not seem to be any apparent reason to believe tether has insufficient resources to meet redemptions. Tether coins in circulation dropped from US$83 billion to US$73 billion possibly amid an erosion of confidence (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tether

Different approaches and combinations thereof to regulate stable coins are being envisaged. Stable coins may be subject to regulation similar to dealing in off-exchange spot foreign currency transactions. Stable coin issuers could be regulated like banks, but banks would likely resist keeping assets segregated and rather leverage their balance sheets whereby a digital coin issued by a bank would be no different than any other bank deposit liability; a narrow bank may constitute a less intrusive version whereby a bank is being constituting only for issuing coins. Stable coin issuers could be regulated like money market funds or a lighter version thereof to allow coins to be exchanged peer-to-peer without the involvement of a broker but would suffice for large value operations. Money transmitter licences could also be used but seem to fall far short of providing sufficient safeguards amid their very limited liability provisions against the large amounts of stable coins in circulation.

Stable coins are conventional monetary liabilities issued under novel conditions. The recent stable coin turbulence could produce two outcomes. Stable coins survive, prove that they can be trusted and the episode will strengthen confidence in the regimes. Stable coins fail and the principles of this generation of stable coins will have to be adjusted. Greater clarity about the regulatory regime for stable coins would help and mapping stable coins into existing regulatory arrangements seems a promising approach. Stable coins serve alternative payment use cases and make available payment instruments across a broader range of financial market infrastructures. They will tend to enrich the current payment landscape.

1 Circuit breakers are employed to avoid precipitous price declines in stock markets by stopping temporarily stock sales. Breaking the buck refers to money market funds that can no longer redeem a money market fund unit at USD1. Gating may be used by mutual funds and other collective investment schemes where redemptions of fund units are suspended to avoid the need for fire sales of assets to meet redemptions.